At dawn on October 14, 1066, two horrifying armies prepared for a momentous clash, each competing for the English throne. The war was fought between King Harold who had ascended to the throne just nine months ago, and Duke William of Normandy, firmly persuaded of his rightful claim to the throne. King Harold positioned their force on the top of a hill approximately 7 miles distant from Hastings. Opposing them, William set their troops across the valley below.

As the sun set on that disastrous day, the battlefield witnessed the miserable scene of thousands of lives lost. The conquering William moved one significant step closer to realizing his ambition of claiming the throne. To explore more this historic battle, continue reading and discover the details of what happened during this iconic moment in English history.

The Battle of Hastings: A Fateful Clash on Senlac Hill

The Battle of Hastings, a thrilling conflict in English history, revolved around the struggle for the English crown between William, Duke of Normandy, and the newly crowned Harold Godwinson (Harold II).

On the 14th of October 1066, King Harold led the English army to Senlac Hill near Hastings, after a tiring march southward after their recent victory. His Saxon forces, tired and reduced in number, faced William’s combined troops.

In the traditional English fashion, Harold’s well-trained soldiers fought primarily on foot, forming a hard protection wall. The battle remained continued throughout the day. On the evening of October 13th, the English and Norman armies found near each other at the location now simply known as Battle. Duke William of Normandy had utilized the immense time to prepare his forces before the battle. In unfamiliar and opposing territory, William’s primary aim was to provoke a powerful confrontation with Harold.

Setting of Positions by the Forces

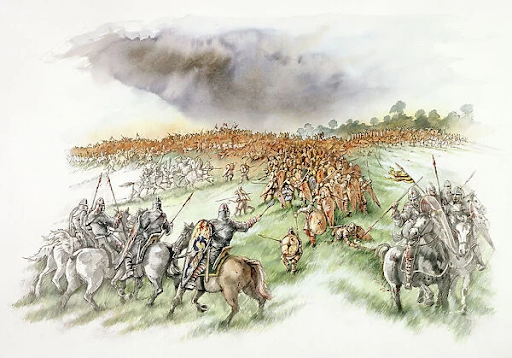

At the break of dawn on the 14th of October, Harold deliberately arranged his forces above the hill, a location now occupied by the establishments of Battle. The English defensive line extended over nearly half a mile and adopted the formation known as a ‘shield wall.’ This formation consisted of soldiers standing closely together, effectively forming a defensive barrier made up of shields. While this formation was highly strong against troops’ charges, it offered limited room for strategic maneuvers.

On the southern side, William extended his army initially on the hillside, overlooking the valley below. His Norman armies occupied the center, with Breton forces likely placed to the west and French troops to the east. William’s army was structured into three ranks: archers at the forefront, followed by the army, and behind them, mounted riders.

Commencement of Battle

At approximately 9 am the battle started with the booming blast of bugles from both sides. For victory, the English strategy was to maintain their protection wall formation, allowing the Normans to maintain heavy losses in repeated attacks. Afterward, they planned to advance and overcome the attacking forces. In contrast, the Normans had to climb the slope to close the distance and come within bowshot range of the English, which was likely a couple of hundred meters at most. Their objective was to break the English line using a combination of archers and army, thus creating an opening for their troops to charge through and destroy the disordered remains of the English forces.

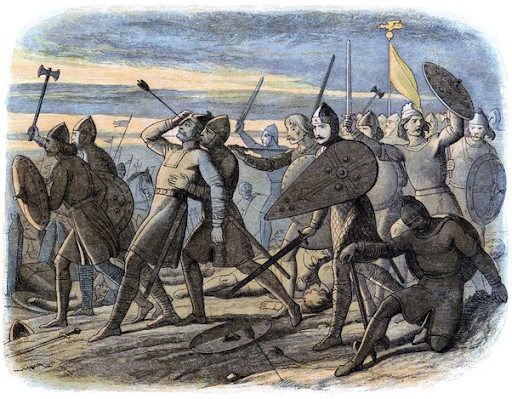

During the battle, Harold’s forces successfully defended the first Norman attacks, with English battle axes making powerful attacks into the defenses of the Norman soldiers, including their protection and armor. However, William’s armies reorganized, and a rumor spread on the left side that the Duke had died, causing some Norman soldiers to panic. In response, English forces began pursuing these exiting Normans down the hill.

To overcome the spreading panic and rebound his troops, William took a brave action by riding out in front of them, raising his helmet to reveal his face, and declaring, “Look at me! I live, and with God’s help, I shall conquer!” This bold move led to a successful counter-charge, as William’s troops surrounded and destroyed the pursuing English forces on a hill, resolving the immediate situation. Throughout the day, the Normans constantly made repeated attacks against the English shield wall.

The Death of King Harold

The battlefield must have presented a miserable scene filled with blood and spread with bodies, arrows, and discarded or broken weapons. The surviving fighters were exhausted, hungry, and fearful, while leaders shouted to motivate their drained forces. As daylight flagged in the autumn evening, the Normans established a final and persistent attack to grab the hill. Harold’s two brothers and other English commanders had already gone.

The critical moment took place when Harold died during this last attack. Unfortunately, King Harold was struck in the eye by a deviating Norman arrow and died on the spot. The battle raged on until all of Harold’s loyal bodyguards were killed. After Harold’s death, the Normans launched a last attack and finally smashed the opponent.

Battle’s Consequences

In an era when battles were resolved within an hour, the outcome at Hastings remained uncertain until dusk, some nine hours after the war began. This emphasizes how evenly matched and well-led both armies were in this historic conflict.

Indeed, the Battle of Hastings marked just the outset of a significant disorder. After his victory, William started on a march towards London, where he was subsequently crowned King of England on Christmas Day in 1066. During his rule, William made many changes to this land. These changes affected the entire range of society, including how it was organized, and governed, its language, legal systems, customs, and particularly, its architectural landscape. Significantly, a surge in castle construction began soon after the Conquest, intended to confirm Norman’s control and power. This historic battle had profound consequences, not only for England but also for the broader landscape of European history. It left a lasting impression on the religious and political institutions of Christendom.